Weighted Least Squares Estimation (LSE)

High Level Strategy

Suppose we want to perform the same exercise of finding the the best-fit linear model for a given dataset as seen in Least Squares Estimation . This time however, let’s also suppose each point in the dataset has some inherent uncertainty.

First of all, what does that mean?

Practical Example: Suppose we have an engine with a non-ideal temperature sensor attached to it. The engine gets hotter with increased RPMs. The engine should always be at the same temperature for the same RPM value, called the true temperature. However, the temperature sensor is non-deterministic, and also has some inherent error.

This means that it will potentially measure a different value than the true temperature at a given RPM, within some statistical range of error. Given its operating range and other conditions, this range might be larger or smaller at different RPMs.

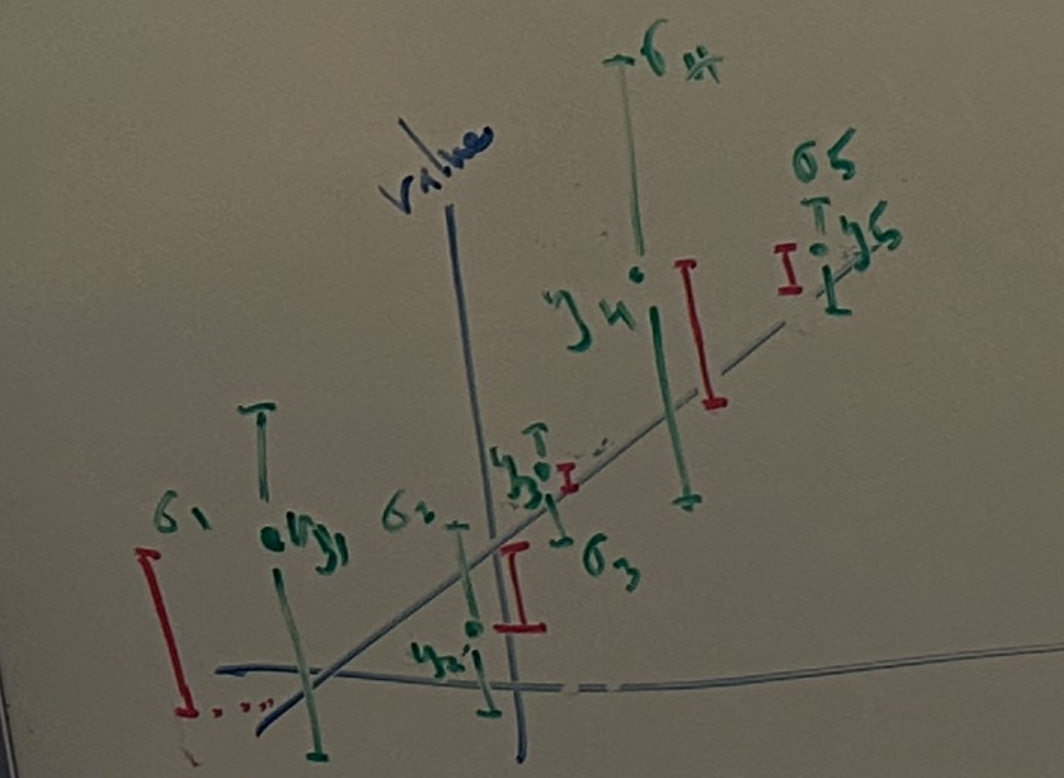

Graphically, we can generally represent this kind of relationship like so:

This diagram looks very similar to that of the general case of the linear best-fit model from the general Least Squares Estimation problem statement. However, note that each data point \((x_i, y_i)\) now has a range of uncertainty \(\sigma_i\). This is saying that \(y_i\) could also fall somewhere in that range for the same value \(x_i\).

Intuitively, \(y_i\) can be thought of as the mean measurement value of a sensor over several readings and \(\sigma_i\) describes the range of values that the measurement could fall within across all the readings.

Next, our linear model can be written as:

\[y = bx + a\]We can then determine an expressions for the residual error at a given point \(x_i\) in the same fashion as the general Least Squares Estimation approach:

\[r_i = (bx_i + a) - y_i\]which can also be written as:

\[y_i = (bx_i + a) + r_i\]Note: the sign changes can be reconciled when the constants are actually calculated. Intuitively, this is generally saying that the value of a given data point is the sum of the model output and the residual error between the data point and the model.

Then, our residuals across all the datapoints can be written in matrix-vector form as a system of equations:

\[\begin{aligned} r_1 &= (bx_1 + a) - y_1 \\ r_2 &= (bx_2 + a) - y_2 \\ &\vdots \\ r_k &= (bx_k + a) - y_k \end{aligned}\]Aside: Random Variables and Modeling Stochasticity

Since we have these notions of means, ranges of uncertainty and non-determinism/randomness, we need some way to work with them mathematically within our model. We can use random variables to handle these notions.

Random variables are used to mathematically express stochastic outcomes as real numbers like so:

\[x : S \rightarrow E\]What is this notation?

- \(x\) is our random variable and can be any real number within the set \(E\)

- \(S\) is the set that contains all the possible outcomes of an experiment

- \(E\) is the set containing all real numbers that can be mapped from the set \(S\)

- Note: once the experiment is carried out, the value of \(x\) has been determined and can be treated as a regular algebraic value thereafter

Next, lets consider the Expectation Operator:

The Expectation Operator \(E(x)\) yields the mean value of the random variable \(x\).

In our considered scenario, the datapoints are stochastic in nature (i.e. having a random probability distribution or pattern that may be analysed statistically but may not be predicted precisely.) we can treat each point as a random variable and apply the Expected Operator to it:

#TODO: do these properties make sense?

- \(E(\bar{R}) = 0\) : unbiased, white noise

- mean of the noise (or residual error) across all datapoints is 0

- \(E({r_i}{r_j}^T) = 0\) : no correlation between datapoints

- mean of the covariance between any two datapoints is 0

As an extension of the above property, we can generate a covariance matrix \(C\), which shows that there is no correlation between the datapoints or between their variances (ranges of uncertainty).

\[C = E({r_i}{r_i^T}) = \begin{bmatrix} \sigma_1^2 & 0 & \dots & 0 \\ 0 & \sigma_2^2 & \dots & 0 \\ \vdots & \vdots & \ddots & \vdots \\ 0 & 0 & \dots & \sigma_k^2 \end{bmatrix}\]Returning to the Weighted LSE Problem

Similar to our approach of minimizing error as seen in Least Squares Estimation, we want to derive an appropriate cost function for the weighted LSE problem based on the overall error (sum of all residuals). However, this time we have datapoints of varying accuracy. Some datapoints could be very noisy, and therefore could even be completely useless. We therefore want our best-fit model to bias towards the datapoints in which we have the greatest confidence.

The simplest way to do this is to inversely scale each component (the residual error of each datapoint) of the overall error based on the uncertainty of that datapoint. The most accurate measurements will therefore be given the greatest weight:

\[\text{Error} = \frac{r_1^2}{\sigma_1^2} + \frac{r_2^2}{\sigma_2^2} + \dots + \frac{r_k^2}{\sigma_k^2} \tag{1}\]We can also note that \(C\) is a diagonal matrix. Thus, its inverse is easily calculated as:

\[C^{-1} = \begin{bmatrix} \frac{1}{\sigma_1^2} & 0 & \dots & 0 \\ 0 & \frac{1}{\sigma_2^2} & \dots & 0 \\ \vdots & \vdots & \ddots & \vdots \\ 0 & 0 & \dots & \frac{1}{\sigma_k^2} \end{bmatrix}\]In matrix-vector form, our error function \((1)\) can be written as:

\[\text{Error} = R^T C^{-1} R \tag{2}\]Note: to see where this expression comes from, see how the Error function is written in matrix-vector form as a sum of unbiased residual components in Least Squares Estimation. We are simply using the \(C^{-1}\) matrix to perform the division operation for each residual component here.

We now want to put the Error function in terms of \(\bar{X}\) so that we can ultimately solve for \(\bar{X}\).

From Least Squares Estimation \((2)\), recall that:

\[% \quad \bar{R} = H \bar{X} - \bar{Y} \quad \quad \bar{R} = H \bar{X} - \bar{Y} \quad\]Thus, our error function \((2)\) can be expanded out by substituting for \(\bar{R}\):

\[\text{Error} = (H \bar{X} - \bar{Y})^T C^{-1} (H \bar{X} - \bar{Y})\] \[\quad \Rightarrow (H \bar{X})^T C^{-1} (H \bar{X}) - (H \bar{X})^T C^{-1} \bar{Y} - \bar{Y}^T C^{-1} (H \bar{X}) + \bar{Y}^T C^{-1} \bar{Y}\quad \tag{3}\]Note that the middle two terms in the above expression are the transposes of each other:

\[(H \bar{X})^T C^{-1} \bar{Y} = \big[\bar{Y}^T C^{-1} (H \bar{X})) \big]^T\]If we consider one of these terms further from a dimensional standpoint, we notice that the matrix multiplication yields a scalar value:

\[(H_{k \times 2} \bar{X}_{2 \times 1})^T C^{-1}_{k \times k} \bar{Y}_{k \times 1} \Rightarrow \text{Scalar}_{1 \times 1}\]and the transpose of a scalar is simply the scalar itself: \(\text{Scalar}^T = \text{Scalar}\)

Thus, we can simply combine the middle two terms in \((3)\) by simply doubling the second of the middle terms like so:

\[2(-\bar{Y}^{T}C^{-1}(H\bar{X})) \Rightarrow -2\bar{Y}^{T}C^{-1}(H\bar{X})\]Our error function can now be condensed into:

\[\text{Error} = (H \bar{X})^T C^{-1} (H \bar{X}) - 2 \bar{Y}^T C^{-1} (H \bar{X}) + \bar{Y}^T C^{-1} \bar{Y} \tag{4}\]Deriving the Best-Fit Model Parameters \(\bar{X}\)

To derive the best-fit model parameters, we want to minimize the overall Error. We therefore follow a similar approach to Least Squares Estimation \((2)\), by deriving the partial derivative of Error with respect to the \(\bar{X}\) and setting it equal to 0.

This will yield the optimal \(\bar{X}\) vector.

\[\Rightarrow \frac{\partial \text{Error}}{\partial \bar{X}} = 0 \Rightarrow \frac{\partial}{\partial \bar{X}} \left( \bar{X}^T H^T C^{-1} H \bar{X} \right) - 2 \bar{Y}^T C^{-1} H\] \[\Rightarrow 0 = 2 \bar{X}^T H^T C^{-1} H - 2 \bar{Y}^T C^{-1} H\] \[\Rightarrow 0 = \bar{X}^T H^T C^{-1} H - \bar{Y}^T C^{-1} H \tag{5}\]Lastly, we can solve for \(\bar{X}\) in \((5)\):

\[\quad \Rightarrow 0 = -\bar{Y}^T C^{-1} H + \bar{X}^T H^T C^{-1} H \quad\] \[\quad \Rightarrow 0 = -H^T C^{-1} \bar{Y} + H^T C^{-1} H \bar{X} \quad\]This yields our final optimized model parameters:

\[\Rightarrow \boxed{ \bar{X} = (H^T C^{-1} H)^{-1} H^T C^{-1} \bar{Y} }\]This looks very similar to the regular LSE solution, except we are now inversely scaling by the variance of each datapoint. This represents the “weighted” component of the LSE.

How does Dataset Uncertainty Propogate to Model Uncertainty?

Given the stochastic element in our datapoints \(\bar{Y}\), we will also have a stochastic element in \(\bar{X}\), our model parameters. Intuitively, we can think of the model parameters as now being more “fuzzy”. This fuzziness can be represented using an uncertainty.

To determine this output uncertainty, lets start with our weighted LSE expression for \(\bar{X}\):

\[\bar{X} = (H^T C^{-1} H)^{-1} H^T C^{-1} \bar{Y}\]We can rewrite this expression in the form \(\bar{X} = A \bar{Y}\) such that:

\[A = (H^T C^{-1} H)^{-1} H^T C^{-1} \tag{6}\]Next, let us consider the general Transformation of Uncertainty, such that for a function \(f = Ax\), if we know the uncertainty of \(x\) (called \(\Sigma_x\)), then we can work out the uncertainty of \(f\) (called \(\Sigma_f\)):

\[\Sigma_f = A \Sigma_x A^T\]We can apply this same approach to our weighted LSE expression. We know the uncertainty of \(\bar{Y}\) to be its covariance matrix \(C\). We have also defined the \(A\) matrix in \((6)\). Thus:

\[\Sigma_{\bar{X}} = A \Sigma_{\bar{Y}} A^T\]For more consistent notation in these notes, we will refer to \(\Sigma_{\bar{X}}\) as \(P\), the uncertainty matrix of \(\bar{X}\), our optimal model parameters. Thus, \(P\) can be expressed as:

\[P = ACA^T\]If we then expand \(A\) from \((6)\), we are finally left with:

\[\boxed{ P = (H^T C^{-1} H)^{-1} }\]